The Western classical music canon is notoriously white and male – so you might assume that a black Renaissance composer would be a figure of significant interest, much-performed and studied. In fact, the story of the first known published black composer – Vicente Lusitano – is only now being heard, alongside a revival of interest in his long-neglected choral music.

More like this:

– How the first pop star blazed a trail

– The singing contest that made history

– The music most embedded in our psyches

Lusitano was born around 1520, in Portugal. In a 17th-Century source, he is described as "pardo" – a commonly used term in Portugal at the time meaning mixed race. It is most likely that Lusitano had a black African mother and a white Portuguese father; Portugal had a significant population of people of African descent, due to its involvement in the slave trade.

Comparatively little is known about Lusitano's life – a fact which has certainly not helped his historical legacy – although what we do know is dotted with juicily intriguing details. "There’s a lot of things you could say about how cool he is as a person, and how exceptional he is as a figure," promises composer, conductor and early music specialist Joseph McHardy, a recent Lusitano champion.

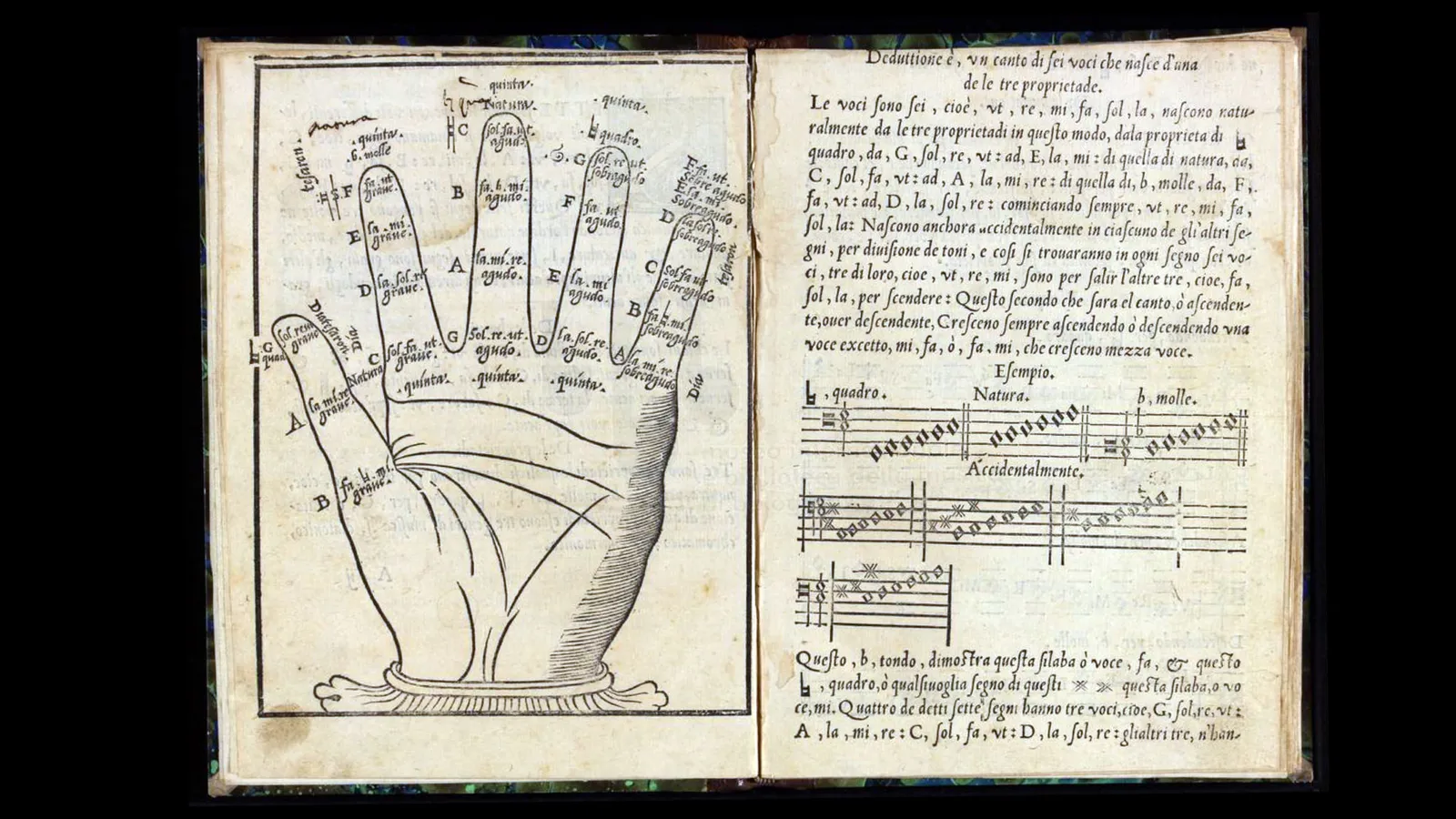

What we do know is that Lusitano became a Catholic priest, composer, and music theorist, and in 1551 left Portugal for Rome – a multicultural musical capital of Europe at the time – most likely following a rich patron, the Portuguese ambassador. Lusitano appears to have done very well for himself there, publishing a collection of motets: sacred, polyphonic choral compositions (where voices sing several layers of independent melodies simultaneously). Then, Lusitano became embroiled in a high-profile public debate around the rules of composition and the use and juxtapositions of different tuning systems or keys, with a rival composer, Nicola Vicentino. Consider it a Twitter spat of the Renaissance age – although with an official judging panel of eminent performers from the Sistine Chapel choir, no less.

In the final adjudication of their intellectual duel, Lusitano was unanimously judged the winner: an unlikely victory given that, as a foreign outsider, he was something of an underdog compared to the well-connected Vicentino. But, unwilling to let it go, Vicentino conducted a smear campaign against Lusitano, discrediting him and his ideas. In what would become a famous, printed 1555 treatise, Vicentino fabricated a misleading version of the debate so it looked like he had the better ideas, really – and it was this document that endured and this version that was later repeated in many textbooks.

Sometime after 1553, Lusitano converts to Protestantism – itself an unheard of development for an Iberian composer in the era. He also gets married, and moves to Germany; we know he receives payment for some music there in 1562, and applied for a job in Stuttgart.

But although his achievements in Rome suggests Lusitano won significant respect for his music in his lifetime, it wasn’t as widely copied or performed as some of his contemporaries, and seems not to have spread across Europe; this has led to some musicologists in Portugal appreciating him, but a failure to cut through among non-Portuguese speaking scholars since. Occasional flashes of academic interest have never transformed into sustained attention, an accessible and readily shareable modern score, or performances of the thing that really matters: his music.

The new Lusitano champions

Until, that is, very recently. During the pandemic, two Renaissance music lovers separately discovered Lusitano, and are staging concerts and bringing out records of his work, while a new piece reimagining a Lusitano composition is currently on tour across the UK.

In what he describes as the "darkest days" of the first lockdown, Rory McCleery – founder of British vocal ensemble The Marian Consort – read an article about Lusitano by an academic, Garrett Schumann from the University of Michigan, in VAN Magazine. Keen to find out more, McCleery was delighted to discover that Liber primus epigramatum, Lusitano's 1551 collection of motets, had been digitised and put online.

"My proclivities have always been in finding Renaissance composers who have fallen between the cracks," he says. "It's always super exciting when you find a composer and start looking into their music and go, actually, this is very good. You want to evangelise about it – music is there to be shared."

And share it, he did: The Marian Consort were including a Lusitano piece, Inviolata, integra et casta es, in concert programmes by December 2020 – probably the first time it had ever been performed live in the UK. Last summer, they weaved it into a Prom celebrating a much more famous Renaissance composer, Josquin des Prez. It was apt, given that Lusitano's work is clearly in dialogue with Josquin – in Inviolata, Lusitano riffed on a hugely technically accomplished five-part composition by Josquin, impressively expanding it further, for eight voices.