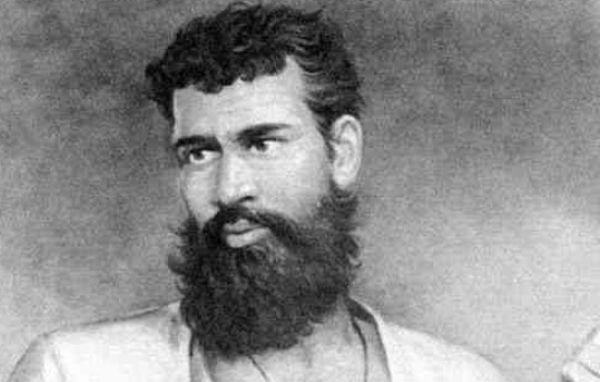

New Delhi: Few in India or China had ever heard of the winding mountain river Galwan that would soon lead them to war. The Galwan Valley, at 5,500 m above sea level, took its name from Kashmiri horse-traders, who once used it to smuggle horses past the customs posts of local warlords.

On 8 July, 1962, a diplomatic note arrived at the Ministry of External Affairs from Beijing, accusing Indian troops of violating the frontier along the river. Earlier, a Chinese military platoon had come face-to-face with a small unit of Gorkha regiment troops, which positioned itself there.

In the note registering a strong protest, China not only asked India for an immediate withdrawal of troops from the Galwan Valley but also warned that it “will never yield before an ever-deeper armed advance by India nor will give up its right to self-defence when unwarrantedly attacked”. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) cut off the Gorkhas from the Samzungling post farther down the valley, cutting off supplies.

On 20 October 1962, PLA units massed along the border and swept into Indian territory, including the Galwan Valley. While the incident at Galwan 60 years ago is seen as the trigger that led to the India-China war, many experts see the fighting as the inevitable outcome of a long diplomatic struggle that had gathered momentum from 1959.

According to Avtar Singh Bhasin’s book Nehru, Tibet and China, the year 1959 “remained the most hectic year in India-China relations, but a great disappointment for India”.

Bhasin notes that the escalation of the revolt in Tibet impacted developments on the frontiers. China — especially its then leader, Mao Zedong — viewed the Dalai Lama’s escape from Tibet in 1959 and his eventual refuge in India as adding insult to injury.

Beijing was also uncomfortable that New Delhi seemed to be asserting British-era borders even as then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru continued with his policy of non-alignment.

Mao claimed the Lhasa rebellion that erupted in Tibet in 1959 was caused by Indians. During his meeting with the then premier of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev, in October 1959, Mao said, “We could not keep the Dalai Lama, for the border with India is very extended and he could cross it at any point.”

Bhasin argues in his book that Nehru’s “fear of losing a friend and appeasing China only whetted the Chinese appetite. India was in consequence left to learn the hard way that fantasising about strength on false premises was a sure recipe for disaster.”

This became clearer when several conflicts and military standoffs began flaring up that ultimately culminated in the border war.

British journalist and scholar Neville Maxwell writes in his infamous book India’s China War that this was all part of Nehru’s well-crafted ‘Forward Policy’, which manifested itself in various ways in the run-up to the 1962 war.

This, Maxwell writes, was rolled out keeping in mind the upcoming general elections prior to the war as the opposition parties blamed Nehru’s government for being soft on China.

“The Indian government’s fundamental border policy of no negotiations [on the border issue] had locked India on a collision course with China in the early 1950s and with the implementation of the forward policy, the point of impact would be reached. But India was still confident that in this titanic game of chicken, it would be China that swerved away,” Maxwell writes in his book.

Decisive incident

While the days leading up to the war saw several military standoffs and border incidents, a decisive clash took place at Kongka Pass, where nine Indian policemen were killed. While India realised after this incident that it wasn’t ready for a war, it nevertheless paved the way for a summit between Nehru and Chinese premier Zhou Enlai — and thus, a window of hope that a confrontation between the two neighbours could be avoided.

The incident took place in October 1959 when an Indian police party, led by an officer of the Intelligence Bureau (IB), was given the task of setting up posts in three strategic locations — Tsogtsalu, Hot Springs and Shamal Lungpa — along the border. They were attacked allegedly by the Chinese troops. While some were killed in the firefight, others were taken prisoner.

“There was no more Hindi Chini Bhai Bhai and it was at this time that Deng Xiaoping argued that India had to be taught a lesson. The incursions into Longju in August 1959 and Kongka in October were most likely meant to probe India’s defences,” writes Swedish journalist Bertil Lintner in his book, China’s India War: Collision Course on the Roof of the World.

Lintner also points out that this was also the time when Mao was in a “shaky position” within the Chinese Communist Party and, thus, in order to strengthen his role, he decided “to use the Tibet issue and the border dispute with India”.

As part of India’s ‘Forward Policy’, notes Bhasin, regular patrolling of border areas began — which also resulted in a rise in incidents on the border. But it wasn’t until the Kongka Pass incident that the Indian population realised the gravity of the crisis. “Particularly after the Kongka Pass incident, the border question received greater attention both inside and outside of Parliament,” Bhasin underscores in his book.

The Nehru-Zhou Enlai summit took place in 1960, but by then the relationship between the two countries was firmly heading southwards. Public opinion began to change and Nehru faced increased pressure. No wonder the summit ended in acrimony, aggravating what was already a worsening of ties.

Why was India inadequately prepared?

The 1962 war was essentially a border war. Both sides differ till this day on the exact position of the border, and even the facts pertaining to the imaginary line are in contention.

While New Delhi’s position is that the Sino-Indian border is 3,488 km in length — which includes the 523 km boundary between Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK) and China — Beijing continues to assert that the border is only 1,700 km, excluding the PoK-China boundary.

According to former diplomat Ranjit Singh Kalha’s India-China Boundary Issues: Quest for Settlement, as public pressure continued to build up on Nehru, on 26 September 1961, the IB submitted a comprehensive report on Chinese activities in the border areas.

The report said, “The Chinese would like to come up to their claim line of 1960, wherever we are not in occupation but where even a dozen of our men are present, the Chinese have kept away.” It also recommended that more posts be set up in the unoccupied areas of Ladakh.

As Nehru ordered Indian foces to move as far forward as possible to prevent the Chinese from entering Indian territory, China began to patrol more aggressively and confront the Indian troops.

On 21 July 1962, for the first time since the Kongka Pass incident, the Chinese opened fire on an Indian Army patrol in the Chip Chap Valley, resulting in two casualties.

This particular incident, according to Kalha — who was fluent in Chinese — was a clear “warning” to Nehru and to the Indian foreign and strategic community at large that “Chinese attitude and policy” towards India had undergone a complete change.

While this posturing by both sides continued in the border areas, in June 1962 Nehru activated diplomatic channels with Beijing to send conciliatory messages that the Chinese leadership dismissed, refusing any form of dialogue on the boundary question.

Meanwhile, Zhou told the Indian chargé d’affaires in Beijing that “China had evidence that the American CIA was financing, arming and guiding heinous anti-Chinese activities. Nehru was either not aware or pretended not to know about such activities against China. India has allowed the installation of modern devices to spy on China.”

But Nehru continued to believe that China would not launch an attack. This was evident in his discussions with then US ambassador to India John Kenneth Galbraith on 6 August 1962, when he said New Delhi and Beijing were planning to hold a dialogue on the border and that “none of the Indian agencies had detected any massing of Chinese troops”.

On 20 October 1962, the PLA invaded India in Ladakh, and across the McMahon Line in the then North-East Frontier Agency. It was called ‘The Day of Reckoning’ by Brigadier John Dalvi, who was captured by the PLA and later penned a war memoir.

“When the final attack came on 20 October, the Indians found that the Chinese had cut all their telephone lines the night before. In preparation for the assault, the Chinese had also taken up positions on higher ground behind Indian defences and were thus able to attack downhill on the morning of the attack,” writes Lintner.

In his book How India Sees The World, former foreign secretary Shyam Saran writes, “India found itself in an unexpected clash of arms mainly as a result of its unfamiliarity with Chinese culture and ways of thinking.”

“Indian leaders failed to pick up cues and oblique hints which if understood accurately may have led to a different outcome than humiliating defeat,” writes Saran, a former chairman of the National Security Advisory Board.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)